Omar Elerian triumphs with his RSC debut, an adaptation of As You Like It which balances both wit and whimsy and levels out at utter fun.

Geraldine James takes the stage as Rosalind, our heroine, cruelly banished from her uncle’s court. Disguising herself in male clothing and adopting the pseudonym of ‘Ganymede’, she ventures into the Forest of Arden after her exiled father, with her closest friend and cousin, Celia (Maureen Beattie). The relationship between these two women is almost more integral to the success of the play than that of Rosalind and Orlando (Malcolm Sinclair). Their unconditional love for one another is a delightful depiction of female kinship, which is often overlooked in light of a romantic plot.

The pair are joined by the court fool, Touchstone (James Hayes, ‘classical actor’), who gives one of the brightest performances in the production. This trio embrace a new style of life in the forest and meet a cast of characters, including the shepherd, Silvius (David Fielder) and his egocentric beloved, Phoebe (Celia Bannerman). The relocation is synonymous with emancipation, and freed from the shackles of rigid courtly routine, the characters find themselves entangled in various and overlapping love plots, in true Shakespearean comedic fashion.

The unorthodox conceit at the centre of Elerian’s adaptation is that the cast are almost entirely septuagenarian. Geraldine James makes her RSC debut at 72, and her onstage relationship with Malcolm Sinclair (73) is filled with sensuality and infatuation, synonymous with the youthful characters in the original text. James’ epilogue draws direct attention to the unconventional practice of centring women in the epilogue, particularly older women. Elerian’s casting is a defence of love and playfulness without temporal limitation, and there is something joyous about witnessing older characters giddy with love.

The premise of the play, as introduced to us by Michael Bertenshaw, who plays Oliver, is that the cast of a 1978 production of As You Like It have regrouped to reproduce their show from memory, without ‘a set or decent prop’. The consequence is that the production takes place in a rehearsal room, with actors who are ‘not on stage’ sitting on chairs at the back of the set, sipping water bottles and laughing alongside the audience as the chaos of the play unfolds.

At first, the metatheatrical element of the play is a little difficult to get into – it takes a moment for the audience to familiarise themselves with the distinction between the Shakespearean character, and the character of the actor, with little costuming to signify difference. However, once this becomes clear, the concept lands spectacularly. The asides from Touchstone as the courtly fool, and from James Hayes as a classical actor, are hilarious, and scattered just tentatively enough so as to not overpower the magic of Shakespeare’s language.

Touchstone’s costuming cannot go without a mention – it was a work of pure genius. The initial ‘no expense spared’ cone hat was wonderful, and the gradual escalations in absurdity never missed the mark. James Hayes (‘classical actor’) was perfectly cast as Touchstone, epitomised by his shining moment onstage while reading through Orlando’s poetry, with his spirited humour simultaneously delighting the adults and the children in the audience.

Praise must also be offered to the youngsters in the cast, who arrived at the rehearsals to fill in the gaps when original cast members could not make it. Laden with their scripts and an eagerness to please, the way Hannah Bristow, Rose Wardlaw, Mogali Masuku and Tyreke Leslie engaged with the older cast members was delightful to see. Over the course of the play, we watch them grow in confidence as actors, and even when they are simply being used as props to mark trees or logs, their presence onstage is humorous and refreshing.

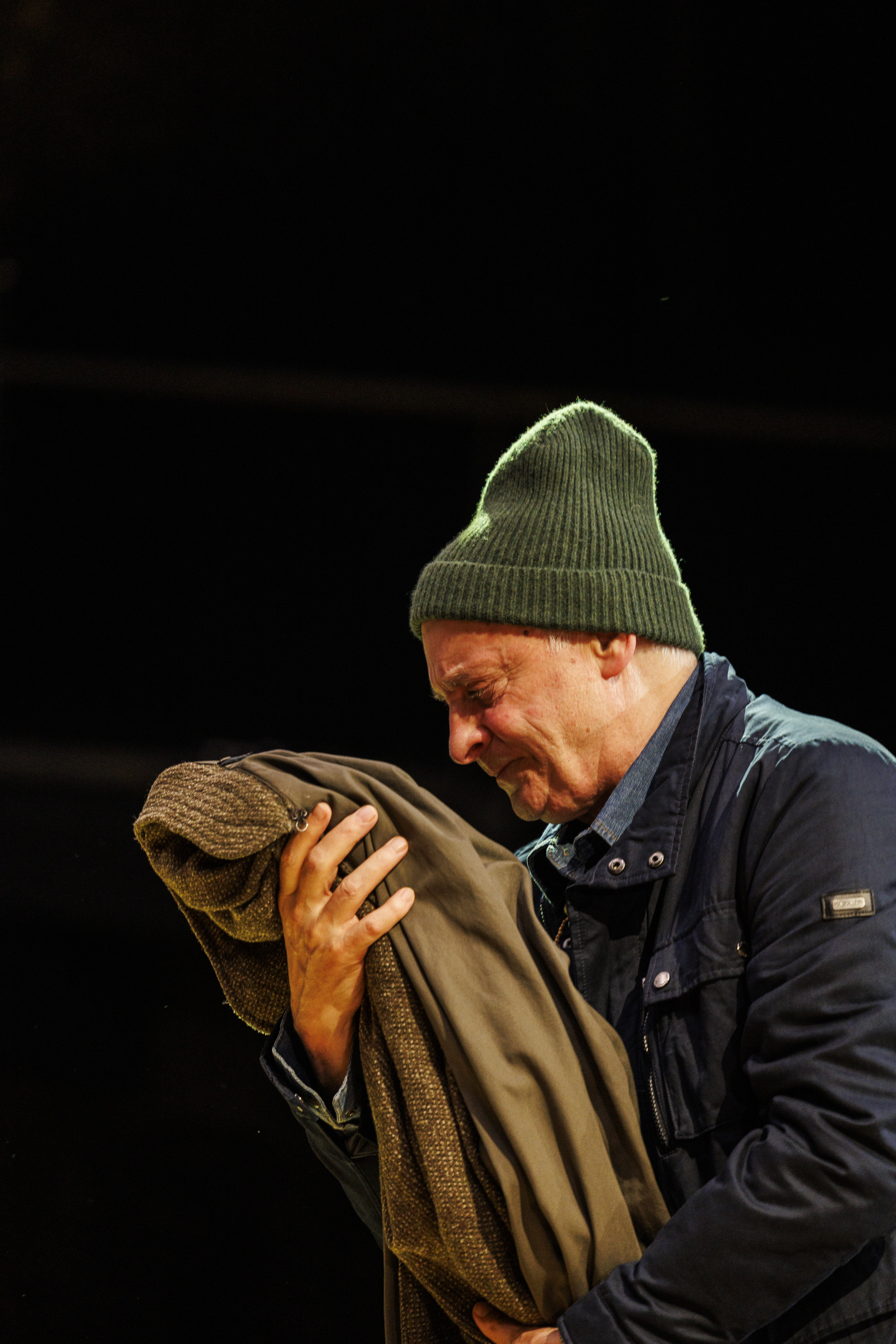

There is something very special about Tyreke Leslie’s interactions with the coat, which represents an original member of the cast who we are told has passed away. This cast member would have played Adam, and the gentleness with which Leslie carries the coat, and delivers Adam’s speech, shows a rare talent.

The metatheatrical interpretation of Adam, wherein we learn that a deceased actor would have played the character who nearly dies in the forest, adds further poignancy to the tenderness shown to him by Sinclair’s Orlando. This is one of many ways in which metatheatre and the older cast enhances the emotional drives from the original text. Orlando and Oliver’s feud is deepened by the presence of older actors, suggesting a longer-standing rivalry. Silvius appears to have been pining for Phoebe dutifully for many years, and the near-death of Adam is filled with an emotional charge reflecting the death of the cast’s former colleague.

Jacques, or Monsieur Melancholy (played by Christopher Saul as the brilliant alternate for Oliver Cotton) is further wisened by the older casting choice – his strongly held views and moral ponderings are cemented by years of serious thought. Stripped back to seated monologues, wearing jeans, Jacques’ words do the talking, and the audience are left to pause for thought amongst the wilderness of the action. This is the effect of the simple, casual costuming across the board – it allows the cast to move smoothly in and out of character, and forces the emphasis to be on their language, and their physicality.

Shakespeare’s As You Like It is perhaps the most quoted play in discussions of metatheatre, and adding an additional metatheatrical dimension was a stroke of genius by Elerian. Whilst one can see that for enthusiasts of traditional Shakespeare, this approach may feel jarring, redirecting attention away from the writing of the bard, I am sure audiences will agree that the cast and crew have masterfully enhanced the essence of Shakespeare. By scaling down the staging, costumes and props, they have amplified his voice, and the thematic concepts which are integral to Shakespearean works.

Romance? Youthful and longing. Comedy? Quick-witted and ironic. Metatheatre? Here in abundance. Social commentary? Absolutely. Shakespearean adaptations have always been about pushing the boundaries of the written word to make the works engaging, and accessible to all. This is not the first RSC adaptation to involve age-blind casting – Iain McEwan’s Hamlet (2021) is a notable example which drew great interest and attention.

The vibrancy of the cast and the poetry of As You Like It have transformative powers of their own – we soon forget that we are in a rehearsal room, and as an audience, are transported to the Forest of Arden, where, in the memories of the returning actors, we have been all along.

Classical Shakespeare fans may take comfort in the knowledge that the second act leans further into the heart of traditional Shakespearean theatre with recognisable costuming, and the rehearsal room begins to melt away with some extraordinary staging choices, which truly must be seen to be believed. The moments of ‘breaking character’ also lessen, as we are absorbed into the play’s culmination.

Ultimately, Elerion’s As You Like It is a beacon of hope for intergenerational Shakespeare. It is not a case of passing the baton from one generation of Thespians to another, but a case of sharing it. The experienced actors guide the young, and they work collaboratively. Age and metatheatre are not hindrances, but strengths. The core joys and emotions in As You Like It know no terms and conditions for applicability, and if all the world’s a stage, I am glad to see older generations are still playing their parts and playing them well. This is Shakespeare as we like it.

★ ★ ★ ★ ★

(As You Like It is running at the Royal Shakespeare Theatre, Stratford-Upon-Avon, from 17th June – 5th August 2023.)